1 Probability Review

1.1 “..common sense reduced to calculation..”

The theory of probabilities is at its root nothing but common sense reduced to calculation; it enables us to appreciate with exactness that which accurate minds feel with a sort of instinct for which often times they are unable to account.

- Pierre Simon Laplace (1819)

1.2 Sample space

We will assume an experiment (or observational process) results in a single outcome (though that single outcome may be as complex as we’d like). A sample space is the collection of all possible outcomes of that experiment. An event is one collection of outcomes in a sample space.

This simple framework is remarkably powerful in terms of organizing our statistical thought.1

1 It also kinda has Kandinsky vibes.

It’s powerful in it’s simplicity: if we’re abstracting the results of an experiment to become a sample space, we’d like it to make some of the structure of our experiment clearer. Events are the collections outcomes that have some meaning in our context. So, for example, let’s consider a context we’ll see in a bit in one of our data sets: imagine we’re considering all of the hate crimes reported in New York over the course of five years. We can take our sample space to be all reported hate crimes during the period. Each reported crime is an outcome (a unique result).

1.3 The arrangement of experimental things

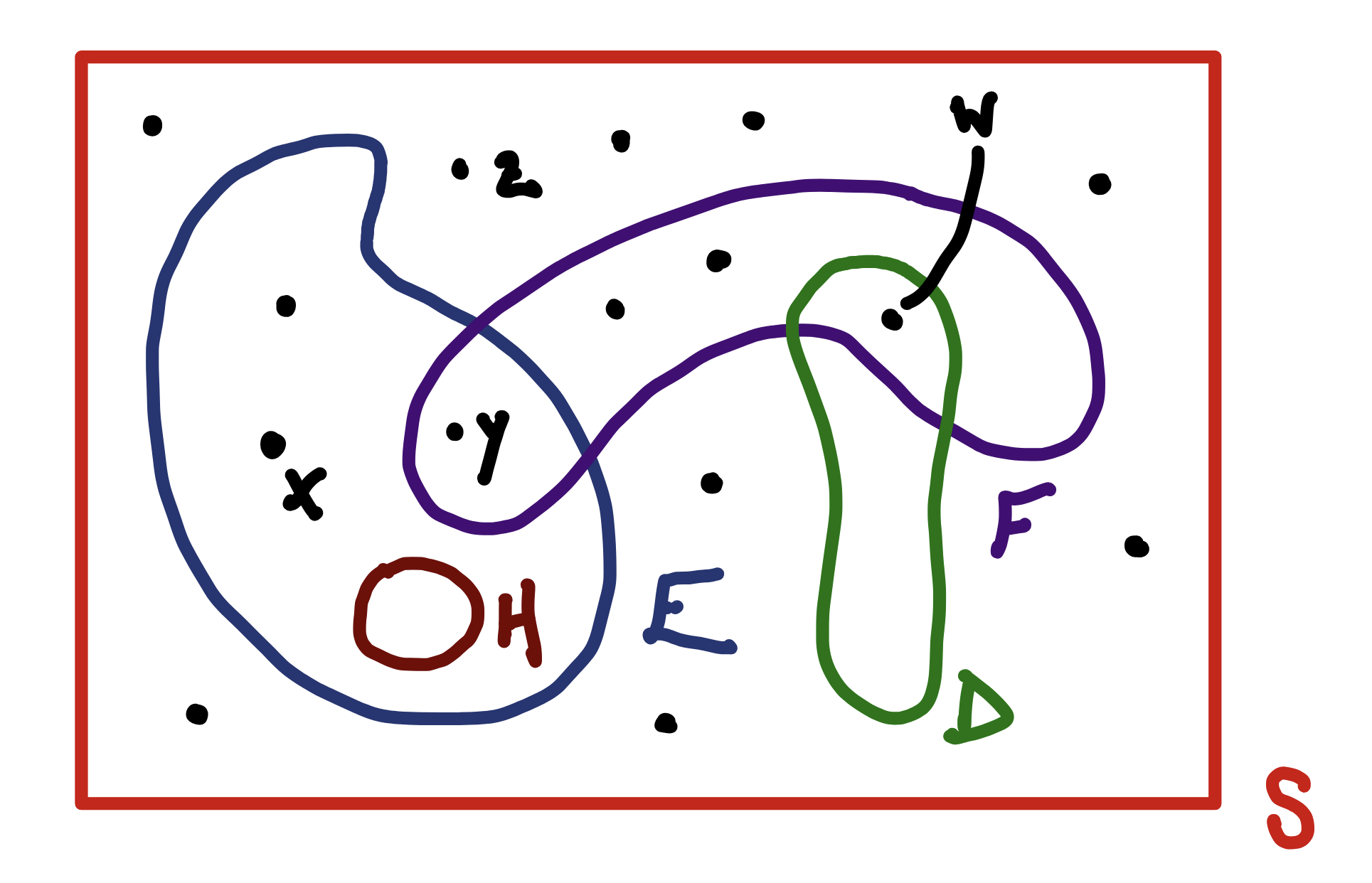

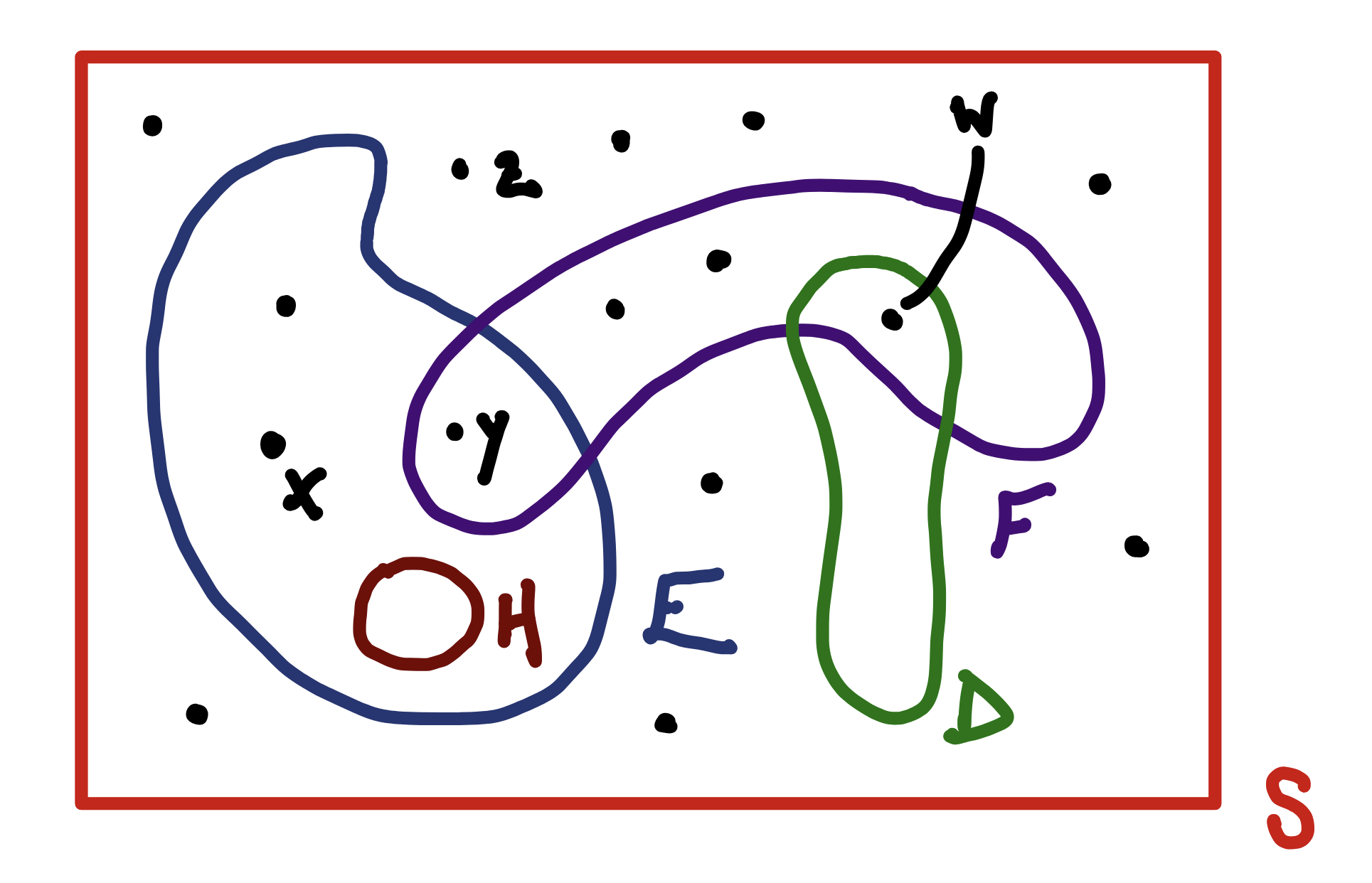

Venn Diagram: dots are outcomes, closed curves are events

- Lower-case letters late in the alphabet are outcomes: \(x, y, w, z\).

- Events are capital letters in the middle alphabet: \(E, F, G\).

- To write an element in an event: \(w \in D\).

- \(H \subseteq E\) means each outcome in \(H\) is also in \(E\).

Visually: containers contained. - It may be that \(H \subseteq E\) and \(H = E\) or \(H \ne E\).

1.4 Operations on events

The goal isn’t just to make events; it’s to work with them:

change them, combine them, remove them.

We do this with event operations!

| Operation | Logic | Math | R Symbol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Union | OR | \(A \cup B\) | \| |

| Intersect | AND | \(A \cap B\) | & |

| Complement | NOT | \(A^c\) | ! |

- Philosophy, mathematics, statistics, computer science all use logic but then often talk about it in slightly different ways.

1.5 Event algebra

When we combine event operations, we need a set of rules — an algebra! — to know what we should do.

Commutativity

- \(A \cup B = B \cup A\)

- \(A \cap B = B \cap A\)

Associativity

- \(A \cup (B \cup C) = (A \cup B) \cup C\)

- \(A \cap (B \cap C) = (A \cap B) \cap C\)

Distributivity

- \(A \cup (B \cap C) = (A \cup B) \cap (A \cup C)\)

- \(A \cap (B \cup C) = (A \cap B) \cup (A \cap C)\)

Identities / idempotence

- \(A \cap A = A\), \(A \cup A = A\)

- \(A \cup A^c = S\), \(A \cap A^c = \emptyset\)

- \((A^c)^c = A\)

- \(\emptyset \cap A = \emptyset\), \(A \cup \emptyset = A\)

de Morgan’s Law

- \((A \cap B)^c = A^c \cup B^c\)

- \((A \cup B)^c = A^c \cap B^c\)

1.6 What we need to remember from probability…

Well, the definition, surely!

In general, we’ll assume we can construct a sample space \(S\) — an abstracted experiment that represents all possible outcomes of an observational process…

…as well as all our usual set-theoretic properties: events, inclusion/exclusion, union, intersection, complement, and the attendant algebraic rules (associativity, etc.).

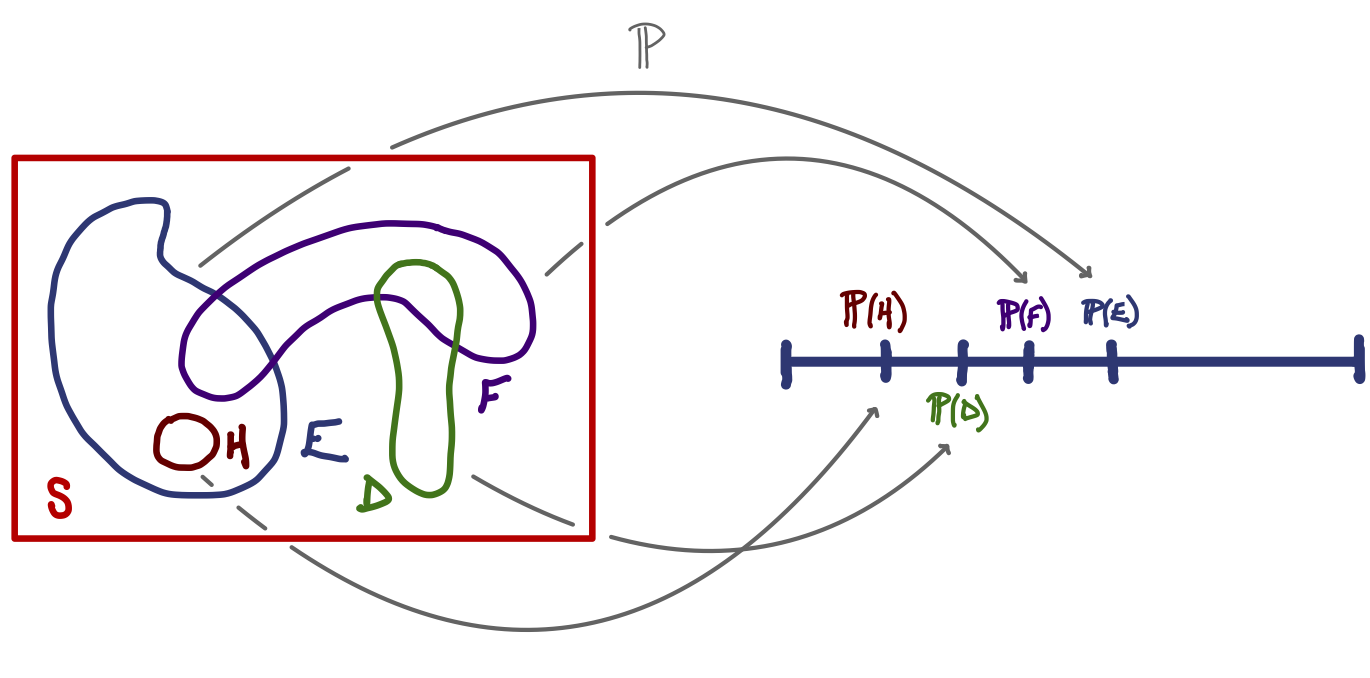

A probability is a function from events in a sample space \(S\) into the real numbers such that for any events \(A\) and \(B\):

- \(\mathbb{P}(S) = 1\);

- \(\mathbb{P}(A) \ge 0\); and,

- If \(A \cap B = \emptyset\) then \[\mathbb{P}(A \cup B) = \mathbb{P}(A) + \mathbb{P}(B).\]

1.7 Probability as a (special) function

We usually think of probability as a measure of uncertainty, which it is. But probability is also a special type of function that takes in events and gives numbers in such a way that the two different algebras work together: it preserves the underlying experimental logic!

Events Numbers

- Building probability models of data sets is one of the primary tasks in this course.

1.8 Simple rules for probability

There are several easily provable statements we’ll use innumerable times through the course:

- \(\mathbb{P}(\emptyset) = 0\)

- \(\mathbb{P}(A^c) = 1 - \mathbb{P}(A)\)

- If \(E \subseteq F\) then \(\mathbb{P}(E) \le \mathbb{P}(F)\).

- For any two events \(E\) and \(F\), \(\mathbb{P}(E \cup F) = \mathbb{P}(E) + \mathbb{P}(F) - \mathbb{P}(E \cap F).\)